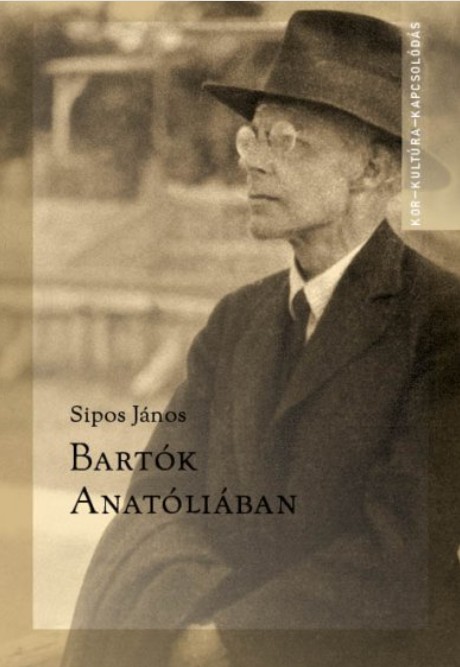

In the footsteps of Bartók in Turkey

János Sipos, a folk music researcher talked about his work in an interview published recently on Napútonline. The turning point in János Sipos's life was when he and his Turkologist wife took up a university position in Ankara. During his many years of residence in Turkey, his attractive life goal with great prospects was formulated: the musical research of the Turkish people. He spent about ten years in Turkish-speaking areas, collecting, and he left a record of more than 10,000 melody recordings, data and comparative analyses on the table of folk music research.

Among other things he said:

At that time, I didn't even know a word of Turkish. And here began a new phase, when my life turned definitively towards folk music research. I knew about Béla Bartók's little-known Turkish collection, and I thought I would try to continue it. During the first semester in Ankara, I learned Turkish, in the second semester I was already employed as a lecturer at Ankara University, then as a teacher, the children settled into the English-language school, and we decided to stay. And we stayed for a total of 6 years. I started researching Turkish folk music, I visited the villages, I had a lot of musical and non-musical experiences, I wrote down, analyzed, and classified the recorded melodies. My years in Ankara were spent in the spirit of university education, family, and above all folk music research – happily. At the end of the Ankara years the manuscripts of my volumes Turkish Folk Music I and II, which provide the first serious overview of Turkish folk music and also discuss Hungarian connections, were ready. From then on I can consider myself an analytical and comparative folk music researcher. After Bartók's volume Turkish Folk Music from Asia Minor, which was based on about a hundred tunes, my works became comparative volumes based on the examination of several thousand tunes with many new discoveries.

He also pointed out:

I am most proud of two results, which can help us understand the Turkish-Mongol connections of Hungarian folk music, and through them certain elements of Hungarian prehistory – of course, taking into account the results of related disciplines. One is that in my volume entitled The Eastern Connections of Hungarian Folk Music I gave an analytical description of almost all living Turkic folk music, with a special focus on Hungarian connections. The other: in the course of the above work a musical map of the vast area inhabited by Turkic and Mongolian peoples stretching from China to Eastern Europe was drawn. It turned out that Turkish folk music is often related to the music of neighboring peoples or peoples assimilated by them. Further south we see strong Iranian connections (Azerbaijani, Anatolian, Turkmen, Uzbek), in the north and east we see connections to the larger pentatonic music of the Mongols (Mongolian and northeastern Kazakhs, Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir), in the Caucasus region we can observe musical interaction with Circassians, Kabardians, Alans and other local peoples, in many cases signs of fusion (Karachay-Balkar, Nogai). The particularly diverse folk music of Turkey undoubtedly also reflects the culture of the assimilated and Turkified Byzantine base layers. The pentatonic zone without a semitone extends from China through the Yellow Uyghurs, the Mongols, a part of the South Siberian Turkic peoples, and the northern and eastern Kazakh territories to the Chuvash, Tatar, and Bashkir peoples living in the Volga-Kama region, and is also characteristic of most older (and some newer) layers of Hungarian folk music. Of the northern and eastern Turkish peoples, essentially only the music of the Yakuts, who arrived later in their present territory and live scattered over a vast area, and some Siberian tribes, is not pentatonic.

He also added:

Béla Bartók went to Turkey in the hope of finding folk songs similar to Hungarian pentatonic melodies. If he did not find the pentatonic style, he did discover the Turkish parallels of the so-called 'psalmodizing' melodies of a significant old Hungarian folk song style (an example of this is the Szívarvány havasán melody). This scientific work of Bartók is very important. It was the first attempt at a scientific-analytical processing of Anatolian folk music. It is quite amazing how the master drew conclusions from this small material, the most important of which have proven to be perfectly correct to this day. We must also pay tribute to the incredibly precise and detailed melodic notations, which - as Kodály characterized Bartók's work - "represent the final limit to which the human ear can reach without instruments". In addition Bartók's research can be classified as one of the earliest field works on Anatolian folk music; The impact of his lectures and collections on Turkish researchers significantly contributed to the revival of Turkish folk music research.

At that time, I didn't even know a word of Turkish. And here began a new phase, when my life turned definitively towards folk music research. I knew about Béla Bartók's little-known Turkish collection, and I thought I would try to continue it. During the first semester in Ankara, I learned Turkish, in the second semester I was already employed as a lecturer at Ankara University, then as a teacher, the children settled into the English-language school, and we decided to stay. And we stayed for a total of 6 years. I started researching Turkish folk music, I visited the villages, I had a lot of musical and non-musical experiences, I wrote down, analyzed, and classified the recorded melodies. My years in Ankara were spent in the spirit of university education, family, and above all folk music research – happily. At the end of the Ankara years the manuscripts of my volumes Turkish Folk Music I and II, which provide the first serious overview of Turkish folk music and also discuss Hungarian connections, were ready. From then on I can consider myself an analytical and comparative folk music researcher. After Bartók's volume Turkish Folk Music from Asia Minor, which was based on about a hundred tunes, my works became comparative volumes based on the examination of several thousand tunes with many new discoveries.

He also pointed out:

I am most proud of two results, which can help us understand the Turkish-Mongol connections of Hungarian folk music, and through them certain elements of Hungarian prehistory – of course, taking into account the results of related disciplines. One is that in my volume entitled The Eastern Connections of Hungarian Folk Music I gave an analytical description of almost all living Turkic folk music, with a special focus on Hungarian connections. The other: in the course of the above work a musical map of the vast area inhabited by Turkic and Mongolian peoples stretching from China to Eastern Europe was drawn. It turned out that Turkish folk music is often related to the music of neighboring peoples or peoples assimilated by them. Further south we see strong Iranian connections (Azerbaijani, Anatolian, Turkmen, Uzbek), in the north and east we see connections to the larger pentatonic music of the Mongols (Mongolian and northeastern Kazakhs, Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir), in the Caucasus region we can observe musical interaction with Circassians, Kabardians, Alans and other local peoples, in many cases signs of fusion (Karachay-Balkar, Nogai). The particularly diverse folk music of Turkey undoubtedly also reflects the culture of the assimilated and Turkified Byzantine base layers. The pentatonic zone without a semitone extends from China through the Yellow Uyghurs, the Mongols, a part of the South Siberian Turkic peoples, and the northern and eastern Kazakh territories to the Chuvash, Tatar, and Bashkir peoples living in the Volga-Kama region, and is also characteristic of most older (and some newer) layers of Hungarian folk music. Of the northern and eastern Turkish peoples, essentially only the music of the Yakuts, who arrived later in their present territory and live scattered over a vast area, and some Siberian tribes, is not pentatonic.

He also added:

Béla Bartók went to Turkey in the hope of finding folk songs similar to Hungarian pentatonic melodies. If he did not find the pentatonic style, he did discover the Turkish parallels of the so-called 'psalmodizing' melodies of a significant old Hungarian folk song style (an example of this is the Szívarvány havasán melody). This scientific work of Bartók is very important. It was the first attempt at a scientific-analytical processing of Anatolian folk music. It is quite amazing how the master drew conclusions from this small material, the most important of which have proven to be perfectly correct to this day. We must also pay tribute to the incredibly precise and detailed melodic notations, which - as Kodály characterized Bartók's work - "represent the final limit to which the human ear can reach without instruments". In addition Bartók's research can be classified as one of the earliest field works on Anatolian folk music; The impact of his lectures and collections on Turkish researchers significantly contributed to the revival of Turkish folk music research.

September 26, 2025